- Home

- Paul Carroll

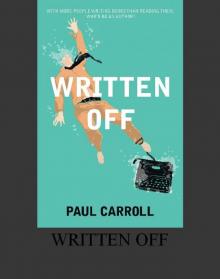

Written Off

Written Off Read online

Written Off

Paul Carroll

Copyright © 2016 Paul Carroll

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador®

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1785895 791

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador® is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

For Sophie

The rain had long stopped and the air was cool. Large puddles from the storm still dotted the piazza and he took care to step around them. As he neared the rotunda he caught sight of a dark shape floating in the water on the edge of the ornamental lake. The flickering overhead sodium light made it difficult to pick out the silhouette and he stepped closer for a better look. As he peered at the unmoving form the buzzing of the damaged light fitting seemed to get louder, as if he was being attacked by a swarm of hornets. Finally, his focus adjusted sufficiently to discern a naked corpse floating face-down in the water.

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

PART TWO

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

SIXTEEN MONTHS LATER

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

CHAPTER ONE

Would Charles Dickens have been as successful an author if another writer with the same moniker had already troubled the bestsellers list? The same could be asked of Enid Blyton, Agatha Christie or Virginia Woolf as unlikely, in their cases, a literary namesake might have been. Surely these writers would have felt compelled to adopt a nom de plume in such a case, if only to avoid comparison, never mind confusion? That this question should pop into the mind of aspirant novelist Eric Blair at this very moment was understandable. A door lay ready to open before him; a fork in the road awaited a footstep either side of the signpost marked ‘success’ and ‘failure’.

While another writer, untroubled by fear of odious comparison due to the name on his birth certificate, opined that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, Eric’s conviction about using his formal appellation for his incipient career as an author was once more beginning to falter. His initial thoughts on the matter had been far from hesitant. First off, it was his name, so why change it? Secondly, he’d adroitly promoted his middle initial, P for Peter, to preclude any mistaken identity, so where was the problem? Thirdly, the handle Eric Blair hadn’t been deemed good enough for the original owner to write under so the way was clear for him. This Eric, for one, wasn’t ashamed of his real name. In any event, in the name game lottery it could have been worse. What if he’d been christened Anthony and was right now being mistaken for the PM who had sent troops into Iraq and Afghanistan, glad-handed Gadaffi and cosied up rather too intimately to the Fourth Estate? Yes, that would have been far more disconcerting.

Eric had long held the belief that his name was an invitation to put pen to paper and to continue a literary lineage of sorts. He was proud of his name and confident in his writing ability. He derived great pleasure from the fact that his first novel had been crafted, chiselled and honed over many years of dedicated endeavour, application and toil (he tended to overlook his abandonment of family duties in this assessment). But to what end? Writing and finishing his opus had been challenging enough. Trying to get it published was an altogether more demanding and difficult proposition. He hadn’t expected it to be this hard. Of course, he told anyone who would listen that it was a very competitive market, that you needed a bit of luck to get an initial break, but deep down Eric truly believed that the call would come his way, sooner rather than later. After all, there couldn’t be that many manuscripts knocking around that matched the genius contained in his. But all he’d received so far was studied indifference. Rejections from literary agents hurt. At first, he affected nonchalance as if he accepted that this was all part of his ‘journey’. His wife Victoria, knowing him better, purchased a sign for his desk reading, ‘Shoot for the moon. Even if you miss, you’ll land among the stars’. Eric, not normally given to twee sentimentality and enduring its presence so as not to offend, was lately beginning to tend towards Isaac Asimov’s rather more downbeat observation that ‘Rejection slips… are lacerations of the soul, if not quite inventions of the devil’.

Of the twelve submissions (the very term denotes capitulation) made to literary agents, so far he’d received back six rejections, all of which, he knew, were standard templates. However, subsequent to these responses (‘response’ in the same sense that a brick thrown through a window constitutes correspondence) Eric was to discover that there was an ignominy far worse than receiving these clipped and cheerless missives; that was not receiving a reply at all. For literary agencies were quite clear in their ‘don’t call us, we’ll call you’ rules of engagement – ‘if you haven’t heard from us in ten to twelve weeks, assume that your submission doesn’t match out needs’.

So, sixteen weeks on from the joyous animation and the giddy ceremony of hitting ‘send’ a dozen times it’s fair to say that Eric’s literary aspirations had received somewhat of a battering. Not that he ever questioned whether his work was good enough – such a heresy never entered his head. Instead he began to ruminate whether the name he’d always considered a blessing was in fact a curse – were these agents laughing at him from behind the crenellated battlements that passed for offices?

There was a reason this thought was uppermost in his mind at this moment. An unexpected event – a ping on his laptop heralding the arrival of fresh tidings, an announcement of note, a vital ‘life or death’ message. Idly, Eric had checked the sender – no doubt urgent advice on how to replace his toners at discount, enlarge his wedding tackle or get laid locally. But no – he could see it was from the Motif Literary Agency. The agency he’d blustered that if he could pick one literary specialist from the modest dozen he’d courted, he’d sign up with them like a shot (subject to terms, of course). And that’s why Eric was hesitating or, more accurat

ely, locked in a temporary state of paralysis. If he opened the email, what would it portend? As he contemplated the bold type at the top of his in-box he realised that it emanated from [email protected] – this response was not being sent to him personally by Motif’s celebrated Hugo Lockwood, the agent Eric had identified at the outset of his quest as being his Svengali-in-waiting. Still, Hugo couldn’t be expected to answer all of his own mail – perhaps he shouldn’t read too much into the sender. It was a reply after all. Still petrified at the point midway between fear of disappointment and entitled expectation, Eric willed himself to click ‘open’.

From the age of four he knew that to read anything he should start at the top, scan from left to right and make his way down to the bottom of the page. This, he understood, would be the most effective method of absorbing the substance of the words now expanding to fill the screen before him. But there’s a curious phenomenon that grips the anxious. Rather like eying one’s dinner plate and deciding to eat everything on it in a single gulp, Eric tried to take in the text before him in one go, to understand its meaning all the quicker. This had the unfortunate effect of trying to read a fruit machine in mid-tumble with the icons reeling and falling in a blur. As the cylinders subsided Eric could finally work out what he’d won. A cherry: ‘Sorry’. A banana: ‘disappoint’. A lemon: ‘not for us’. He was going to have to play again. And all without the aid of a nudge function.

Hugo Lockwood was late for his lunch appointment and cursing under his breath as he burst through the door of the Lamb and Flag in Covent Garden. There, sitting awaiting him in the corner, was Emily Chatterton who at least appeared to be preoccupied as she deftly tapped away at her mobile phone. Hugo immediately suspected that she was announcing his tardiness to the rest of the planet. In the pecking order of the literary world an agent being late for an appointment with the Editorial Director of a leading publisher wasn’t normally a brilliant career move so he was relieved to see Emily’s smile on spotting him, immediately removing any fear of recrimination for his lack of punctuality. In any event, it was Emily who had called for this ‘quick get-together’ at short notice so formality wasn’t the priority here. Hugo and Emily went back a long way and considered themselves friends – not unusual in an industry where constantly letting your friends down was par for the course.

Kisses on cheeks, apology, acceptance of apology and condemnations of London traffic out of the way, the two relaxed. Hugo didn’t yet know the purpose of the meeting. When Emily emailed the previous afternoon to enquire if he was around this lunchtime his Pavlovian response was a straightforward ‘yes’. As a senior player at Franklin & Pope, one of the biggest publishers he dealt with, she wouldn’t want to see him for anything trivial so it would be impolite to enquire as to her agenda. Despite the hierarchy at play there was a tacit understanding of their mutual dependence – he sold his authors and their books to her, so she was the client; she’d buy from him but still shop elsewhere while making sure she didn’t get pipped by a competing publisher when he had a real gem to offer. It was complicated in the same way a professional gambler courts a racehorse trainer – the inside info increased the odds of cleaning up but you could still spill your guts on ‘guaranteed’ tips.

The choice of this ‘quick-lunch’ rendezvous was also of interest. Not a restaurant which might denote a deal celebration, a fervid planning session or a softening up exercise ahead of a pre-emptive bid. A pub, where he’d have a quick chicken, bacon and guacamole sandwich and a single pint of Frontier and she’d order the feta, hummus, tomato and watercress sandwich with a small bottle of Perrier. Practical, utilitarian, businesslike. While they awaited their order there was no attempt to tackle the reason they were there – protocol dictated that this would wait until napkins were discharged. Instead they talked about the brave, possibly northern, patrons who were availing themselves of the outside tables on this sunny but chill Spring day, and of the latest amusing cat video on Vine. When the food arrived Hugo moved the discussion back towards publishing by describing, in comic detail, the attire and antics of several of Emily’s competitors he had encountered at a party hosted by Orion the previous evening. Emily was all ears. Hugo then raised next month’s London Book Fair – his way of inviting Emily to tell him what Franklin & Pope were planning to do for his authors.

Finally, Emily was ready. At least she didn’t beat around the bush. ‘Hugo, I’m afraid I have some disappointing news. We’re not going to be taking up our option on Reardon’s final book.’

Hugo’s expression betrayed that he’d not factored this possibility into the many equations he’d formulated since receiving Emily’s lunch invitation. Reardon – Reardon Boyle – was one of Hugo’s most renowned authors and had sold steadily over the years. For Christ’s sake, he’d won critical praise from the broadsheets, had seen one novel turned into a TV series and currently decorated his work-study with at least two lumps of plastic that passed for awards these days. Emily was giving Reardon – and therefore him – the bullet? Hugo knew, from his days of being bullied at school, that it wasn’t helpful to show pain even when one was dying inside – it tended to encourage further treatment being dished out. ‘Really? I’m surprised,’ he croaked as the disappointment thrust his head down the toilet bowl.

Emily, having ripped off the plaster in double quick time, could now afford to be concilatory. ‘Listen, Hugo, it’s been a very difficult decision for us to make. And when I say “we”, I have to tell you that I personally fought tooth and nail against this.’

Hugo ignored this last comment to proffer a weak, ‘But he’s selling well?’

‘He’s selling steadily rather than “well” and steadily isn’t enough these days, Hugo, you know that. Existentialism is dead. It’s not where it’s at these days. We don’t think taking up our option on the final book makes sound economic sense.’

Hugo suppressed his urge to argue, despite the bitterness he felt at this unexpected dousing. Not least because he had other authors with Franklin & Pope to worry about. ‘That’s very, very disappointing news. Reardon will be devastated.’

‘We could be doing him a favour, Hugo. Think about it like that. You’ll place him with another publisher who can give him the sort of support we can’t at this moment. This could turn out to be a really good move for him.’

Hugo looked rueful. Adroit in the art of deflection he smiled and said, ‘Well I’ll tell him, of course. Can’t give everybody good news all of the time.’

‘Thanks, Hugo. I knew you’d understand.’

And Hugo did understand, knowing that the ripple that had just washed over him emanated from the rather large rock Emily had dropped into the Franklin & Pope pool eighteen months before.

‘Spring is a time of plans and projects,’ chirruped Chapman Hall, a man never far from a literary quote. The entrepreneur was in upbeat mood since he was about to start putting the flesh on the bones of his greatest achievement, his biggest love, the annual ‘The Write Stuff’ conference for unpublished writers. His PA, Suzie Q (an inevitable nickname given her baptismal name of Susan Quixall), sat opposite him with three bulging files – one red, one yellow, one blue – laid out neatly on his desk. Mindful of Chapman’s ongoing struggle to constrain his stomach within the ever-tightening waistband of his trousers she had been out to buy calorie-counted prawn mayonnaise sandwiches and fruit pots from Marks & Spencer for their working lunch. She had also ensured that there was skimmed milk to accompany the large pot of coffee she’d prepared. The rest of the staff at The Write Stuff knew better than to disturb them over the next two hours.

Chapman, momentarily disappointed that there were no hand cooked vegetable crisps on hand to bulk out his lunch, got down to business. ‘Right, Suze. This is going to be the most successful Write Stuff conference to date. You know how we’re going to do that?’

Suzie thought for a second. ‘By keeping to last year’s prices?’

Suzie looked up at the huge, framed poster on the wall created for last year’s conference. Back then the theme was markedly different. Chapman’s sales mantra twelve months ago had all been about creating belief, desire and expectation, the art of the possible and the wind of change. Chapman’s face, copying the iconic Shepard Fairey poster of Barack Obama, stared back down at her. Beneath it the word ‘HOPE’ remained unaltered. She scribbled down ‘fear’ on her notepad and underlined it three times.

Chapman loved authors. He positively adored them. In particular he reserved unqualified and abundant affection for writers who had yet to step up to the big time and get a publishing deal. Helping to transform these literary ugly ducklings into swans was the reason he’d set up The Write Stuff ten years ago. And what a move that was turning out to be. In contrast to the publishers and agents whose golden age was now a fond remembrance, The Write Stuff continued to make a killing on the back of the burgeoning market of wannabe writers, all desperate to get into print. For Chapman, it was like shooting fish in a barrel – no matter what new services or events he created ‘to help authors find an agent’ or ‘to become a better writer’, they would come forward in increasing numbers to seek his wisdom, happy to pay big money to do so. But the market was starting to get crowded as new competitors and national broadsheet newspapers tried to cash in on his territory with their own writing seminars, talks and workshops. Chapman knew he had to keep a step ahead and above all, keep polishing The Write Stuff’s halo at every opportunity. Credibility was everything in this game.

Written Off

Written Off